Maybelline Murphy wandered into the Saco Reny’s on a hot August afternoon. She hated to turn on the air conditioning during the day, saving it for those hot nights when she couldn’t get comfortable no matter what. Electric kept going up and her fixed income didn’t let her use it just any time she felt like it. The store was cool and not crowded and she slowly made her way around the aisles. There were some clearance racks and she flipped through the things in her size, none of it very much her style. The assortment was tired and picked over, some defects here and there, unsuitable for the cold weather to come and for her age. She wasn’t about to wear a hot pink tank top. Where would she wear it? At home in the hot apartment perhaps. Well, at night maybe. It was only ninety-nine cents. If it didn’t say Hot Chick on it maybe she’d get it. Oh, she was that all right, but not the way they meant it.

She pushed her cart around, looking at the other women’s clothes. Then she moved through the men’s section. No harm in looking. This store didn’t have the painful memories the JC Penney’s in Portland had for her. John had been alive then and she’d bought him clothes there, hankies to briefs to work shirts to overalls. Flannel shirts and winter coats and socks and work boots. When he retired they’d go there together and he’d look at it all but never wanted to buy anything.

“I have more than enough, May. What do I need with another shirt?”

“For church?” She’d said once. But he never went. What she’d really thought was for laying him out someday, but never got around to getting a new one. A yellowing shirt in the closet had looked fine under his one suit with a wide tie when the time came. Only a few people came to the wake as it was. The family was so scattered, and their only child Johnny was down south in the military and she didn’t want to ask him to come and he didn’t offer.

But these aisles didn’t make her think of John. She’d moved down here from Munjoy Hill into a senior housing building when a social worker had helped her find a new place to live after John died. The rent kept going up and rattling around in there without him broke her heart. Not that they had been all that happy, but they’d made a go of it, got along well enough and had each other for company.

Now she made her way through the food aisles. She put some jam in the basket, a box of mac and cheese, and some tea bags. After walking around she put it all back. She had unopened jars of jam as it was, and she didn’t really like macaroni and cheese. Johnny did and she had a thought of having it in case he visited, but she hadn’t heard from him in years. Oh, the kids didn’t like to write letters. They liked email and texts, her neighbor had told her, but she didn’t use either. She called him but he never answered, so she’d ask him to call her back, but he never did. Maybe it wasn’t even his number. The voice was mechanical and just said to leave a message. She put back the tea because she still had a big box from an earlier shopping trip.

The housewares aisles were more interesting. Clotheslines and clothespins, of which she had plenty, and in an apartment building you didn’t hang a line. But she’d strung one in her bathroom with a thing with suction cups she’d found at Reny’s one year. She hated to spend money on those washers and dryers in the laundry room. It was just as easy to wash out her underthings and small household things in the tub or sink. Sheets and towels she took downstairs as infrequently as she dared. Every couple of weeks or so. In the winter when they gave good heat she could bring things up damp and drape over furniture and on her bathroom line until they were dry enough to fold and put away.

So many things to buy. Various paper products, cheaply made pots and pans, can openers, corkscrews, and bottle openers, decorated kitchen towels and potholders, trivets, placemats, pillows and bed linens. Tourist stuff with Maine all over it.

Foil liners for your stove burners to cover up the dried up boiled over milk. But a box of soap pads kept under the sink with her rubber gloves lasted for ages, and she had all the time in the world to scrub off any spills. In fact that sort of job was something to do, and she enjoyed the satisfaction of a shiny stove top. She’d put on the radio and listen to music or talking or news. It was a kind of company. Like the TV, but you didn’t have to keep going into the living room to see what was going on. You could listen and know what it was all about while you worked. Dusting, mopping the floor, doing her laundry, such as it was, things like that, managed to take up a lot of the day.

In good weather, walking was a great time filler. Maybelline would tie on her sneakers and tucking her keys in a pocket, she’d set out for the beach if she had the energy to make it that far. Even if she didn’t, she could get a good walk in before turning around for home. She usually wore one of John’s old fishing caps to shade her face. The doctor had told her to use sunscreen and wear a hat. She used the sunscreen sparingly and had bought a huge bottle at Reny’s last year that would probably last longer than she did.

She strolled around the store, reluctant to go home. She didn’t need wrapping paper, greeting cards or toothpaste. Or calendars or makeup or shampoo. She didn’t need spaghetti or soup or oatmeal. She didn’t really need anything. Just something to do. They didn’t really sell that, but actually they gave it away for free.

She was about to leave when she saw a table of clearance items near the registers. Everything bore an orange tag with a nice low price. Dented cans of soup, a calendar eight months old, some tube socks, and a box marked “CD boombox” that looked like a clock radio from the picture on the front. It was about a foot square. She picked up the box and looked at it. It advertised an am/fm radio, a CD player, and a digital clock with alarm. She had never had anything like it. Years ago they had a cassette player but neither of them liked buying cassettes. They had record albums and an old hi-fi to play them but the last time it needed a new needle, they couldn’t find one and had stopped using it. One year Johnny took the records away, saying he could sell them. If he did, she never heard about it.

She set down the box. What was the point? She had a radio and a clock in almost every room. She had the portable color TV sitting on top of the hi-fi console they had saved for all those years ago. She read magazines and catalogs left in the mail room downstairs and picked up the Press-Herald on Sundays so she’d know what was going on. As she was gazing back at the box, a man’s voice rang out.

“You gonna buy that?” It was Jerry Feldman from down the hall. “I got one. It’s a box. Don’t know about the boom,” he guffawed. “$9.95” isn’t too bad, I guess. Paid a lot more than that when I got mine a few years ago.”

She felt herself go red with self-consciousness. “I don’t have any CDs,” she offered lamely as he stared at her expectantly. “I don’t really need it.”

“Well, I can solve that one for you. Got tons of them I haven’t even listened to yet. Do me a favor if you’d take some. Bring ‘em back if you don’t like them. Try some new ones.” His face lit up as he spoke. “Really!”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said, anxious to get away and out of the store. They’d only said hello as they passed one another or took the elevator at the same time in the years she’d lived there. But she looked back at it again. The colorful label indicated fun might be had with it. “Okay,” she said as she lifted the box and carried it to the checkout.

Jerry said he’d see her back at the building after he was done shopping, and he headed off down a food aisle. The checker asked if she needed a shopping bag but she always had a fold up one in her purse. Unfolding it proved it too small for the task, and she said she’d just carry her purchase to the car.

Heading out through the store’s vestibule with the box in both hands she passed a younger woman just going in, carrying a wad of folded shopping bags. The woman somehow looked well-off, casually dressed in shorts and a pink tank top. No words on it though, and not quite hot pink. Maybe it was her handbag that said money somehow. What was she doing shopping here when she could probably go to Hannaford, or Costco or wherever else? The woman smiled, and she seemed to look at the box in Maybelline’s hands with interest. She felt like saying it was the last one, but didn’t feel comfortable doing that, so they each went their separate ways.

May got to the car and set her purchase on the passenger seat as she started the motor. It coughed a bit but finally got going and she headed back to her apartment. What was she thinking, she asked herself. Jerry Feldman? Not Catholic either, but what did that matter to a hill of beans, as her mother used to say. A nice enough guy but probably a little younger than she was and not sure if he was widowed or divorced or a confirmed bachelor. He dressed well enough in clothes that always seemed cleaned and pressed. He had always been friendly and she had always rebuffed him. Until today.

After dropping off her purse and purchase at her apartment, she walked to Jerry’s door. He greeted her just as she touched the doorbell, as if he’d been watching out the peephole. Maybe he had been. That gave May a start and she considered turning back. But it was too late. He ushered her into his apartment. She immediately could see it was bigger than hers and beautifully furnished with sleek furniture right out of a magazine.

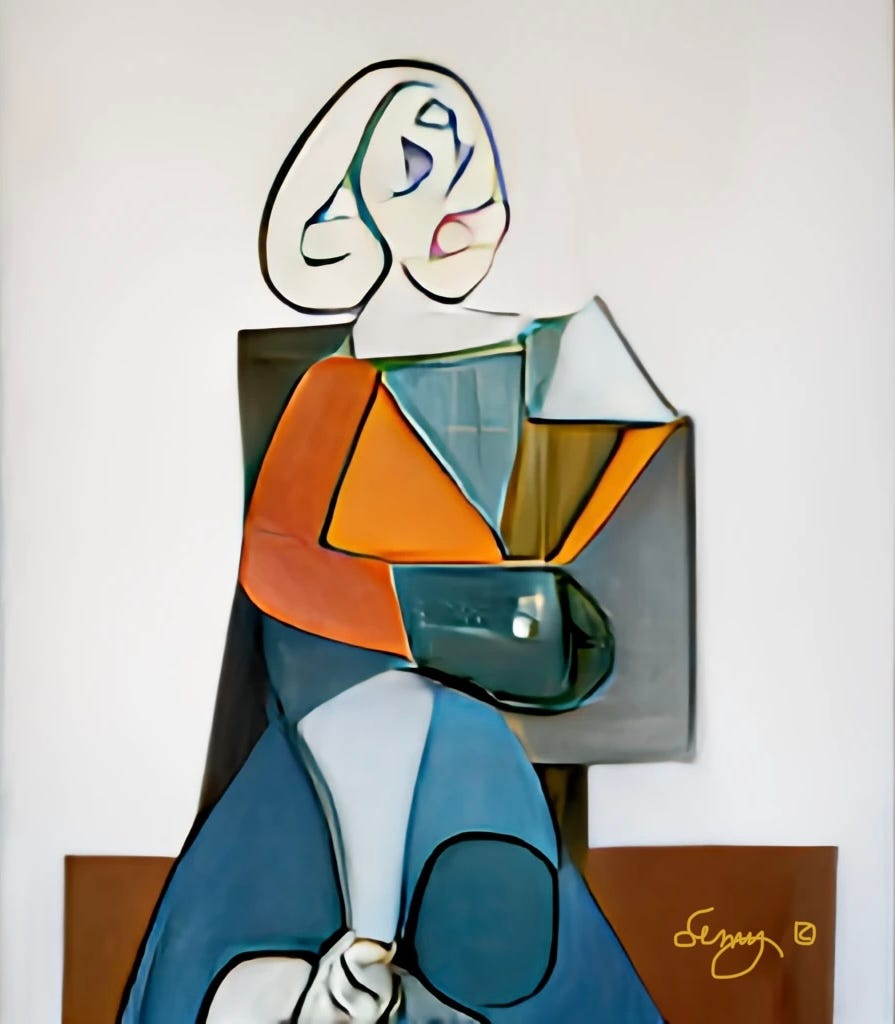

“My goodness, Jerry, this is nice.” She felt embarrassed that this was all she could figure out to say. She started looking around and he seemed at ease with her doing that, so she looked at everything, walking around and stopping before each painting. One was very colorful but she found it strange, too.

Jerry came up next to her as she looked at the painting.

“Do you like it?” he asked.

“I suppose I do, but I don’t understand it. What is it supposed to be?”

“It’s a Picasso, of a woman he knew, his mistress actually. A good lithograph from 1955 I was fortunate to find online. It’s called ‘The Dream’. I first saw it at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and have always loved it.”

May looked at him. Jerry? Who is this man? Picasso? New York?

“I guess you lived there?” she asked, lamely, not sure why she cared but realized she was curious. He nodded.

May had been to New York once as a child, visiting her mother’s sister and her husband in New Jersey who had brought their family into Manhattan to show them the sights. They had taken a ferry boat to the Statue of Liberty and then gone up in the elevator to top of the the Empire State Building. Well, she knew it wasn’t really the top, but as high as you could go. Uncle Jack had played tour guide, driving them into the city in his Cadillac and making a big deal of paying a lot for parking, treating them to a fancy dinner at a place called Lüchow’s. It turned out to be a German restaurant, a source of embarrassment to her father who had tried to act sophisticated by saying how he liked Chinese food and rattled off the names of a few favorite very Americanized dishes like chop suey. Her mother tried to laugh it off but May never forgot the awkwardness of the whole meal.

They were Mainers, her grandfather a potato farmer from way up in the County, and her father had been drafted into the army during the Second World War and hadn’t wanted to go back. But when his father died suddenly of a stroke he and his brothers had gone up to try to help his mother and that’s when he met her mother, who had been vacationing at a lakeside resort where he worked part time summers as a handyman.

His brother Jake took over the farming operation, a fact her father had found a relief but also a source of some shame that he hadn't wanted to join in the business. Her grandfather had always spoken of the boys continuing his legacy as a successful farmer. His grandfather had immigrated from Ireland where his family had farmed until the famines. He’d had the experience and the know-how. It was an obvious choice. Land had been cheap then, so he’d purchased 200 acres and made a real go of it.

May’s father had opened a hardware store in Portland that supported their family well enough but she had no interest in taking it over when he retired. They had sold it for a good price to a chain. Sadly, her mother developed dementia and her care had taken up all the profits from the sale and more, so by the time she died there was no inheritance for May to cushion her own later years. She lived a very spartan lifestyle now, and made her social security income stretch through living in senior housing and shopping at dollar stores and Reny’s.

May was so deep in thought she didn’t even see the interesting painting anymore. Suddenly music was playing, Benny Goodman. She turned around and Jerry was standing right behind her.

“Wanna dance?” he asked with his hand out.